Deep Vein Thrombosis.

Rationale.

THE QUESTION: IS THERE A DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS?

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a common problem worldwide, affecting ≈1 per 1000 adults annually (4). Around one-third of patients presenting with a symptomatic DVT will later manifest a pulmonary embolism (PE), while 90% of all PEs originate from a DVT. In the UK, PE is responsible for killing approximately 8000 people per annum, and, in reality, the incidence of both PE and DVT is probably much higher due to significant under-diagnosis (1). As a result, it is essential to implement effective tools for early and accurate diagnosis of DVT; also ensuring a timely treatment.

WHY USE ULTRASOUND?

Although a painful or swollen leg is a frequent complaint in the ED, a textbook clinical presentation of DVT accounts for no more than 20% of cases and remains non-specific. Hence, clinical examination alone is unreliable, and further investigation is often required. A radiologist-performed ultrasound (US) is the first-line diagnostic test for detecting lower limb deep-vein thrombosis. However, as this requires coordination with a different service, patient transfer, and waiting for the report, it is time-consuming and impractical in the ED setting. Additionally, is often only available in-hours or not available at all.

In this context, the whole-leg standard US has been simplified into a two-point compression US that is easy to learn and rapid to perform, decreasing the demand on the Radiology Department and optimizing costs and patient flow in the ED. More importantly, when paired with D-dimer and validated prediction score, namely the wells score, it provides a reliable diagnostic tool at the point of care (5). Moreover, the accuracy of emergency physician-performed ultrasound for the diagnosis of DVT has proven to be high and comparable to the reference standard, showing both sensitivity and specificity superior to 96% (6).

LIMITATIONS

The now classic two-point DVT assessment is a narrowed-down exploration of the common femoral and popliteal veins, as such its main limitation is missing DVT in other locations. More recent evidence involving a large cohort of patients with confirmed DVT showed that 6.3% of them had thrombi in proximal veins other than the common femoral and popliteal (7). These results support the idea that sonographic assessment for DVT in the ED should also include the superficial and deep femoral veins. Also, as calf veins assessment is not part of the routine examination, another limitation of two-point compression US is missing isolated below-knee DVT. As such, some authors even propose the sonographic exploration of the whole extremity in the ED (2).

Alternatively, it should also be considered that patients with previous venous disease, including DVT, may have incompressible veins, resulting in a false-positive result.

Lastly, bear in mind that compression ultrasound does not rule out DVT on its own and works as an adjunct to clinical reasoning, prediction tools, and D-dimer. Hence, the decision-making process should always be a combined strategy.

In DVT the major health risks are propagation and/or embolization. The risk of embolization in a patient who may have below-knee DVT, but with no evidence of proximal DVT on compression US, is quoted as between 0.7% and 1.1%. However, the risk of propagation of below-knee DVT is quoted as ranging from 2% to 36%. Therefore, patients who have normal three-point compression testing, but who are at high risk for DVT as defined by a validated clinical assessment tool, should have a repeat scan at approximately 1 week. Local treatment protocols should be followed as regards indication for anticoagulation during this period (1).

POCUS-based algorithm for DVT assessment in the ED. Basaure et. al [2]

Anatomy.

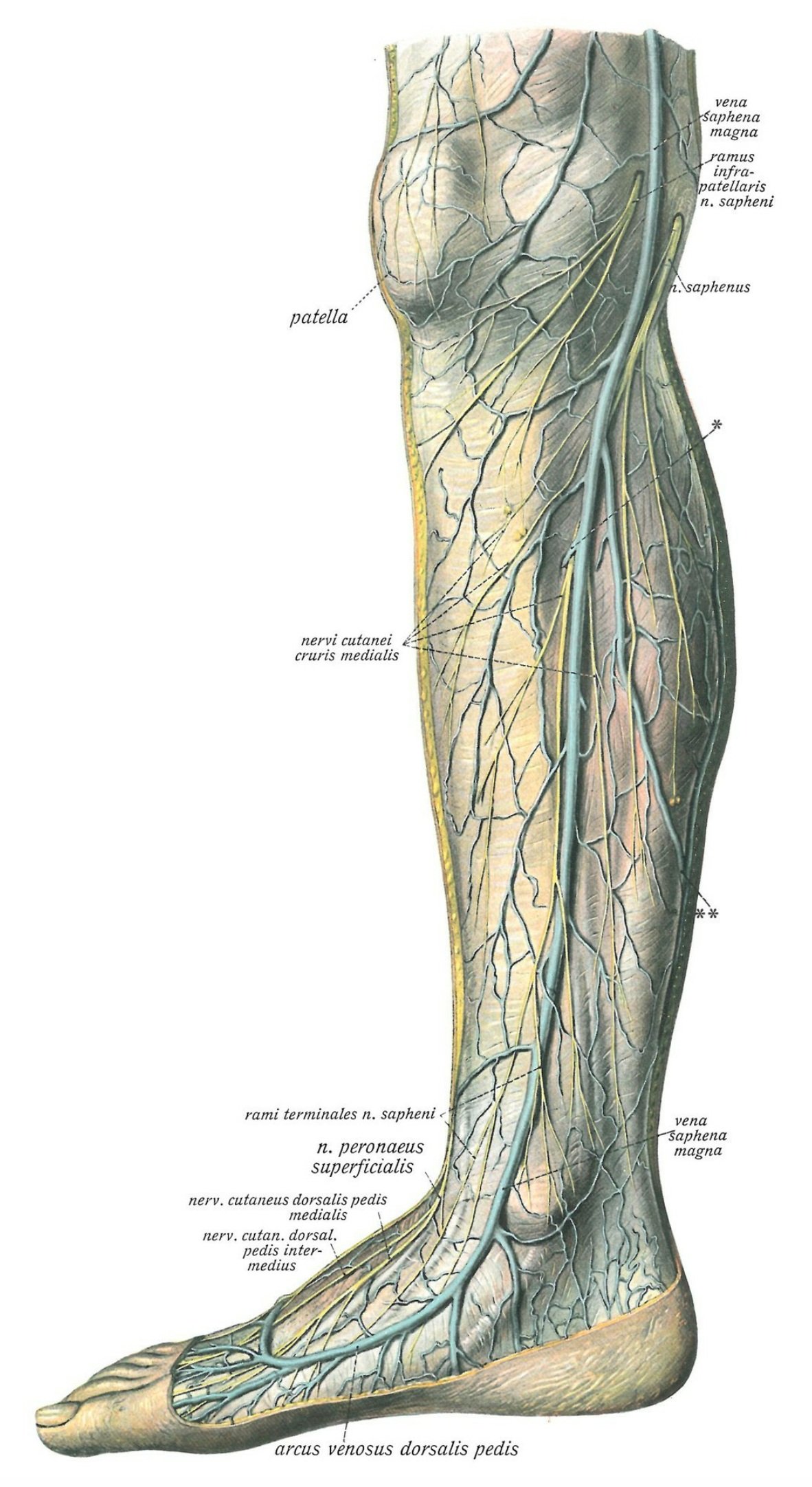

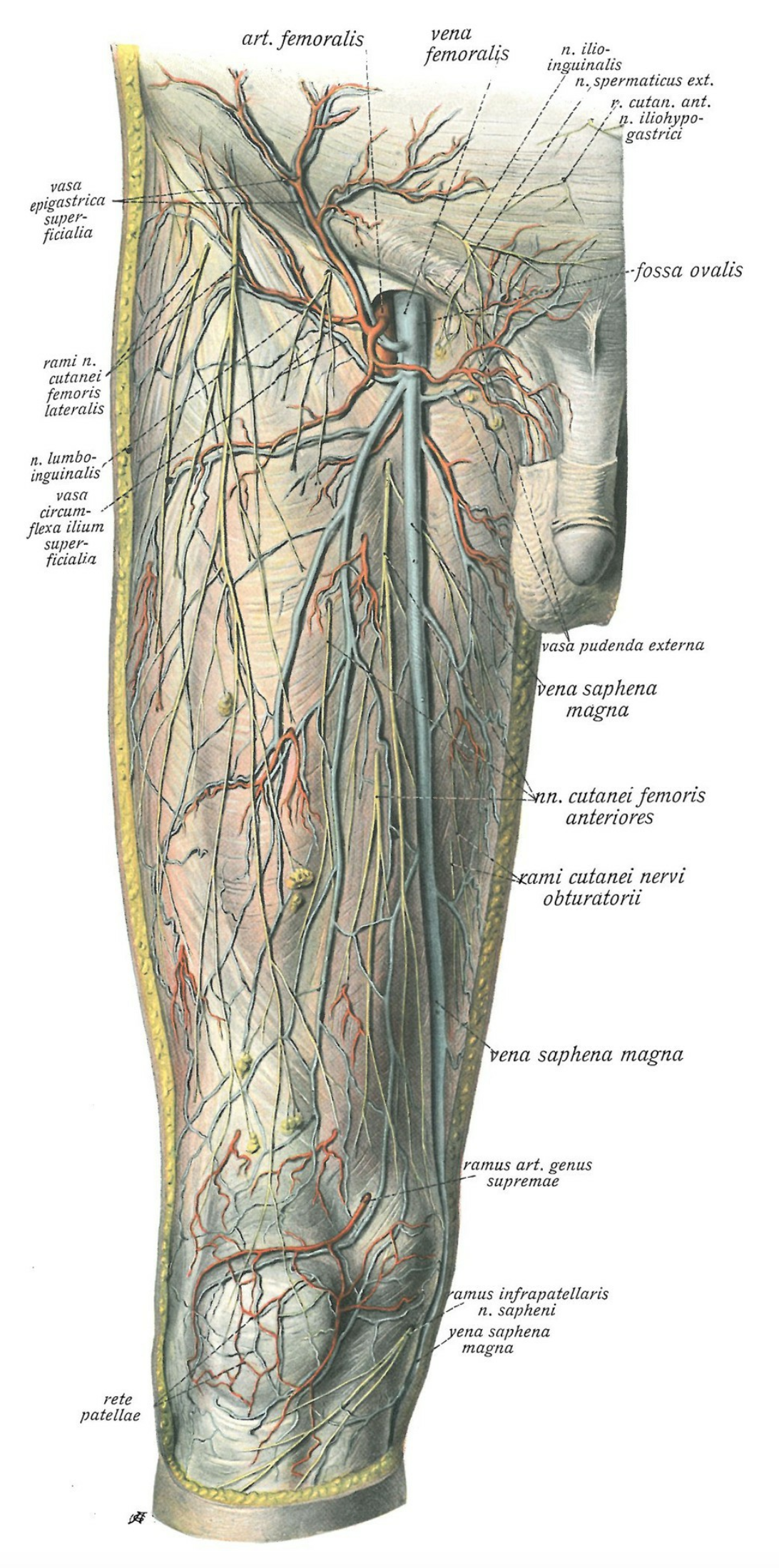

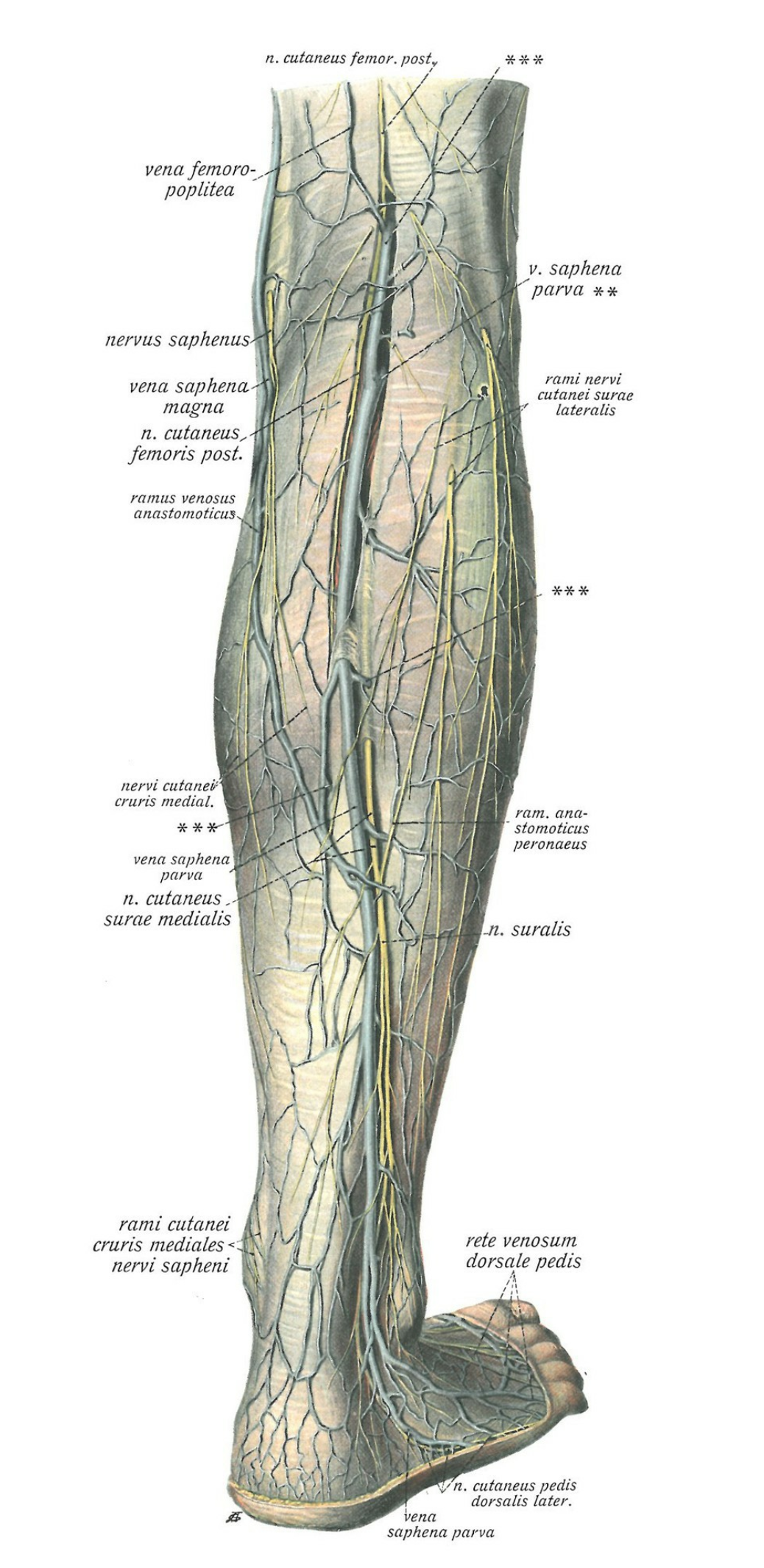

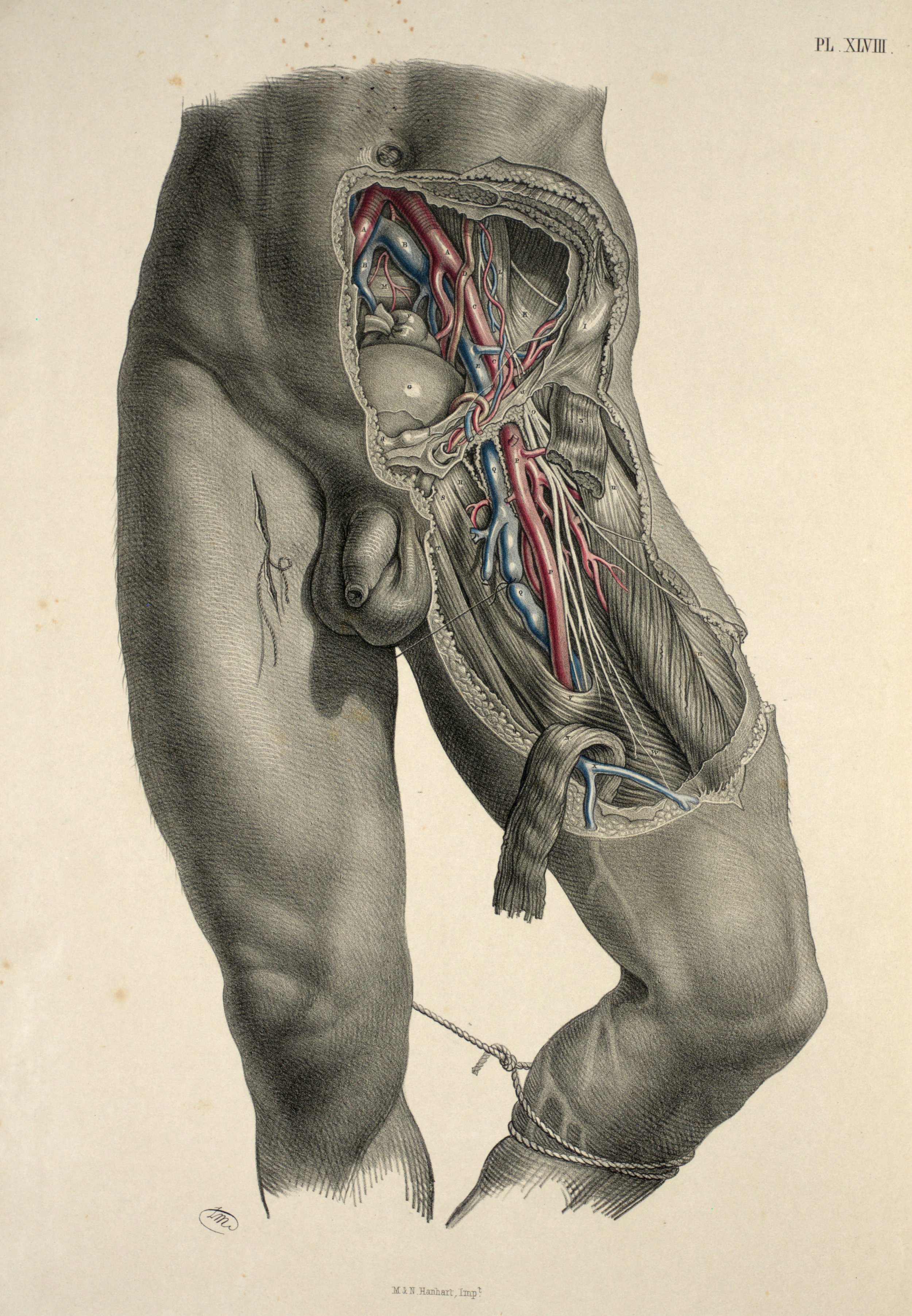

The venous distribution in the lower extremity is comprised of both a superficial and a deep venous system. The superficial medial region of each leg drains into the Saphena Magna, which ascends along the leg and into the thigh to join the proximal femoral vein (saphenofemoral junction) below its entrance to the inguinal canal. Meanwhile, the lesser saphenous vein, which then joins the popliteal vein, gathers blood from the superficial, posterolateral region of the leg.

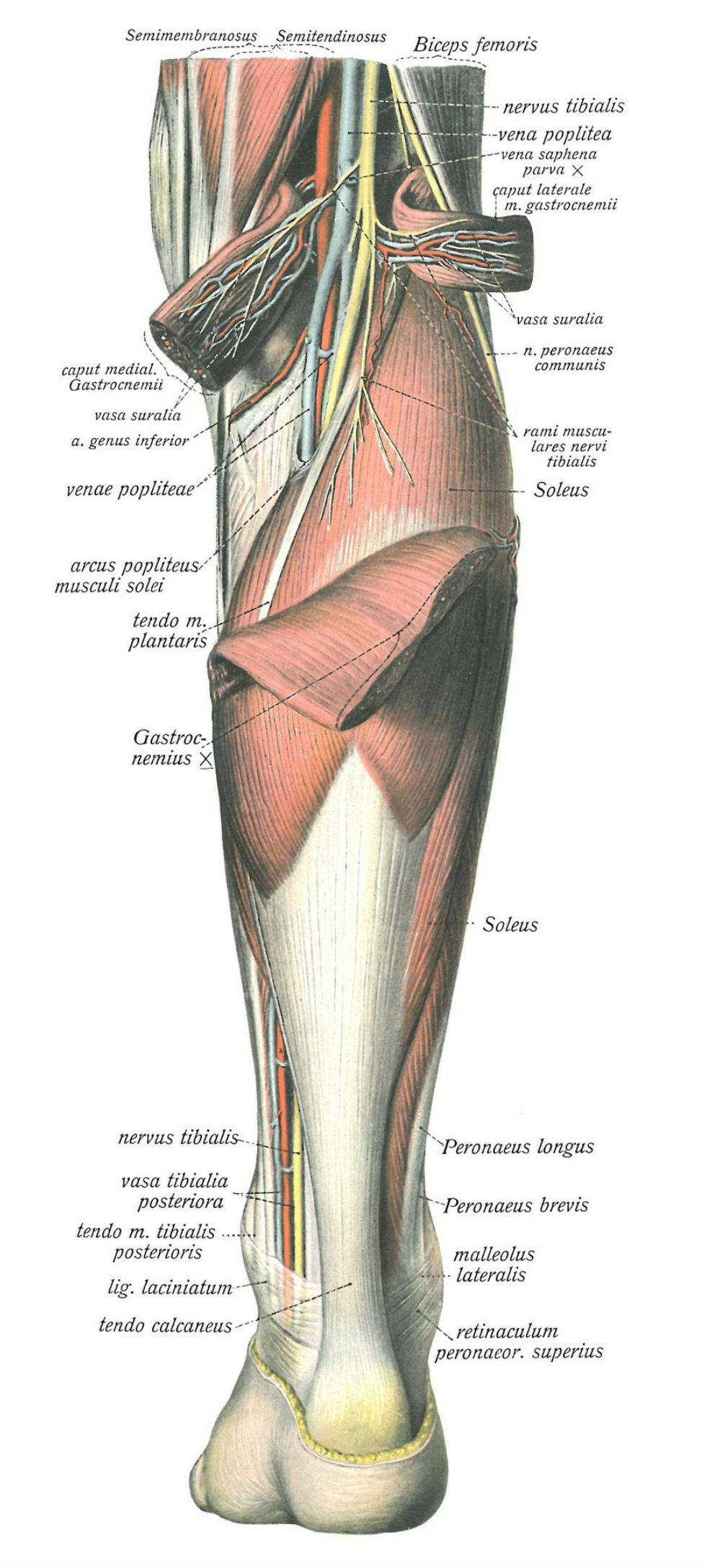

The popliteal vein begins behind the knee as the confluence of the deep calf veins. In the popliteal fossa, it lies superficial to the popliteal artery and ascends through the adductor canal into the thigh, becoming the femoral vein.

The femoral vein lies anteromedially in the thigh: initially deep to the femoral artery and medial to it as it ascends. The confluence of the profunda femoris (approximately 4 cm below the inguinal ligament) forms the common femoral vein which transforms into the external iliac as it passes superiorly under the inguinal ligament. Despite also being called “superficial”, the femoral vein is actually a part of the deep venous system and has a tendency to thrombus formation, so it should be scanned distally into the thigh until its passage through the adductor canal.

Technique & Views.

PROBE

The high-frequency, linear array probe is ideal, as it provides high-resolution images and sufficient depth. The depth should be set to 3-4 cm so that the vessels are centred on the screen. Adjusting the gain allows a clear distinction between the anechoic lumen of the vessels and their hyperechoic walls. It is fundamental to scan at a right angle to the long axis of the vessel, as this will improve the image and more importantly avoid oblique views and misestimations. A normal vein will be deformed and collapse under mild compression with the probe, so excessive force is not needed.

POSITION & VIEWS

Theoretically, a 40º degree reverse Trendelenburg position favours the visualization of the venous continent, but this might be impractical in the ED.

On the leg of interest, a minimum of three views/clips must be obtained, and all of them should be clearly labelled with the side and the anatomical site: Saphenofemoral Junction, Distal Femoral Vein, and Popliteal Vein. Additionally, each clip should be taken with and without compression.

GROIN TO ADDUCTOR CANAL

The 3-point compression test begins with the assessment of the common femoral vein (CFV). The patient remains in the supine position while the hip is in external rotation and the knee in slight flexion. The probe scans transversal to the long axis of the vessel, pointing the marker to the patient’s right. The mark on the screen is traditionally in the left corner.

Place the probe just below the inguinal ligament and identify the Saphenofemoral Junction or “Mickey Mouse” sign. Although the Saphena Magna belongs to the superficial venous system, it has a highly turbulent flow with a predisposition to thrombus formation, which translates into a high risk of thrombus extension to the common femoral vein.

Consequently, the saphenofemoral confluence is a critical part of the assessment, and to dismiss it equals an incomplete exam. Then, follow the CFV distally, compressing each 1-2 cm and identifying the confluence of the profunda femoris. Lastly, follow the distal femoral vein as it slides along the thigh until it reaches the adductor canal.

POPLITEAL SEGMENT

The patient can remain in supine position with a externally rotated hip and gentle knee flexion, or be examined in a lateral decubitus. Consider, however, that technique and interpretation errors are frequent when acquiring the popliteal view, particularly by sonographers under training.

As such, a prone position with reverse Trendelenburg can be useful to avoid these mistakes. Placing a pillow under the leg provides a slight flexion that removes the tension on the popliteal fascia and vein. Do not apply excessive pressure as vessels in this area are more sensitive to it.

Once the patient is in position, start in the proximal region of the popliteal fossa. At this level, the popliteal vein is typically superficial to the artery. Slide the probe superiorly to the adductor hiatus and inferiorly until the confluence of the calf veins, compressing each 1-2 cm.

Pathology.

If at any point the vein is seen to have echogenic material within the lumen and/or is found to be incompressible, then the examination can be terminated as the patient has a DVT at this site. However, it can be useful to complete the scan at the 3 points to map the extension of the DVT.

Differentials.

As discussed at the beginning, a painful or swollen limb is a frequent complaint in the ED, and the clinical presentation of DVT is nothing but non-specific. Multiple conditions can cause limb pain or swelling, and a negative DVT scan is not equal to absence of pathology. Consequently, it may be a wise strategy to have a syndromatic approach to these symptoms, keeping the list of differentials wide.

Unilateral causes of limb swelling: An illustrated differential Diagnosis by Dr Ciléin Kerns [8]

Author: Felipe Urriola Perez | Published: 16 September 2022

Reference.

Bowra, Justin; McLaughlin, Russell; Atkinson, Paul; Henry, Jaimie. Emergency Ultrasound Made Easy, Third Edition. 2022. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Basaure, Carlos; Clausdorff, Hans; Riquelme; Felipe. Ultrasonido Clínico, First edition. 2018. Emergency Medicine Residency Program, Universidad Católica de Chile.

The Pocus Atlas. https://www.thepocusatlas.com

White RH. The Epidemiology of Venous Thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(90231):4I--8. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

Bernardi E, Camporese G, Büller HR, Siragusa S, Imberti D, Berchio A, Ghirarduzzi A, Verlato F, Anastasio R, Prati C, Piccioli A, Pesavento R, Bova C, Maltempi P, Zanatta N, Cogo A, Cappelli R, Bucherini E, Cuppini S, Noventa F, Prandoni P; Erasmus Study Group. Serial 2-point ultrasonography plus D-dimer vs whole-leg color-coded Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1653-9. PMID: 18840838

Pomero F, Dentali F, Borretta V, Bonzini M, Melchio R, Douketis JD, Fenoglio LM. Accuracy of emergency physician-performed ultrasonography in the diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2013 Jan;109(1):137-45. PMID: 23138420

Adhikari S, Zeger W, Thom C, Fields JM. Isolated Deep Venous Thrombosis: Implications for 2-Point Compression Ultrasonography of the Lower Extremity. Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Sep;66(3):262-6. PMID: 25465473

Artibiotics. https://artibiotics.com/