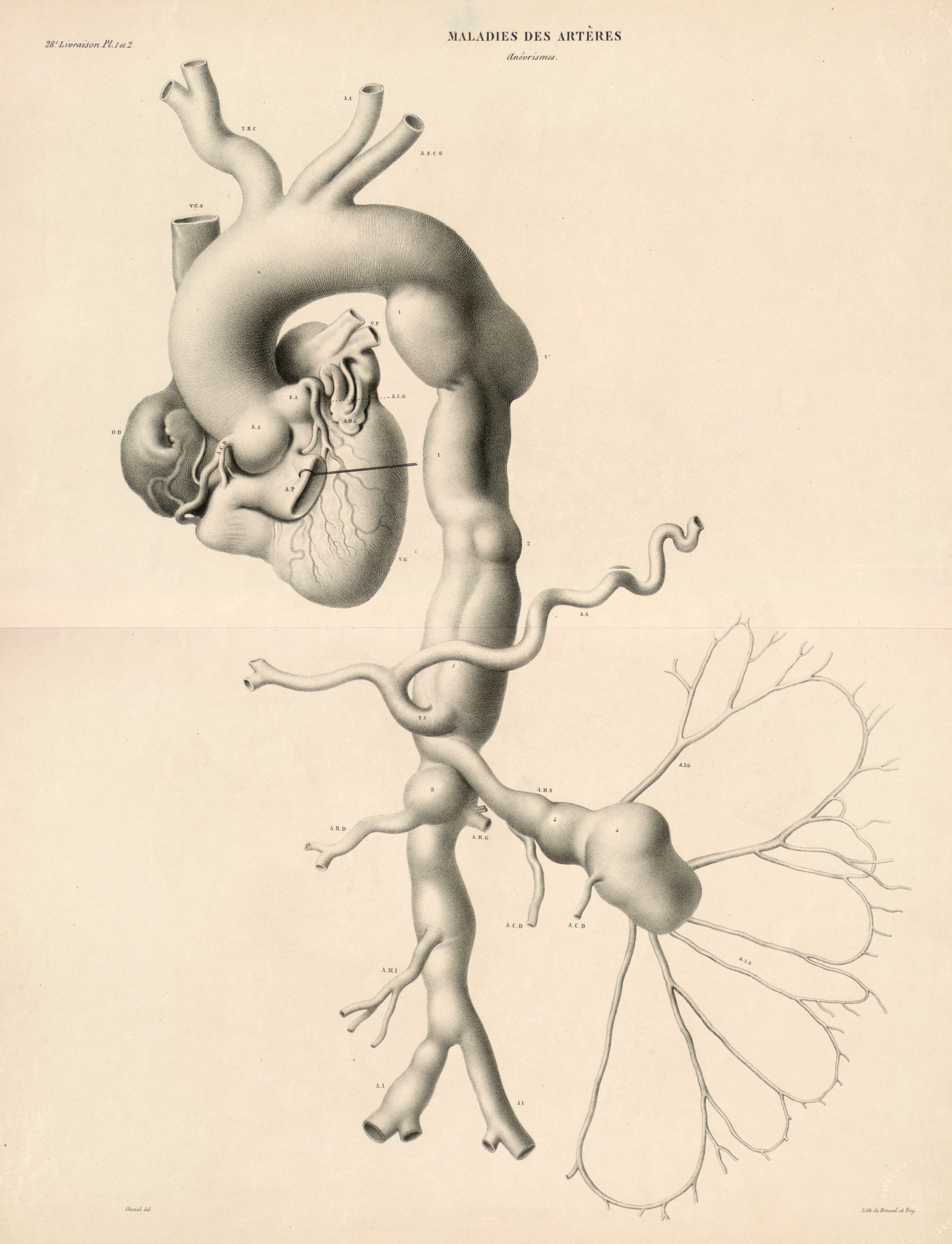

Abdominal Aorta

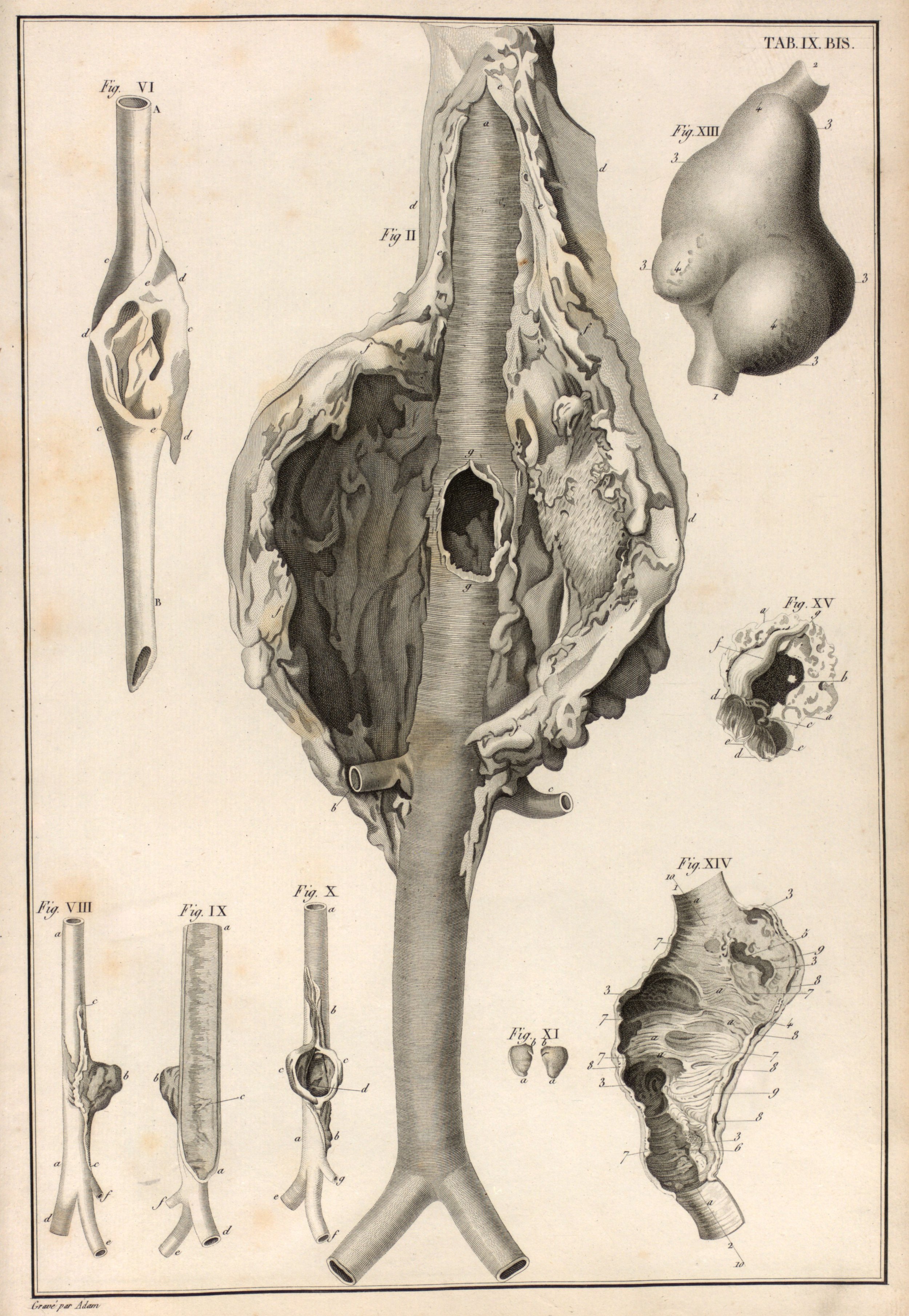

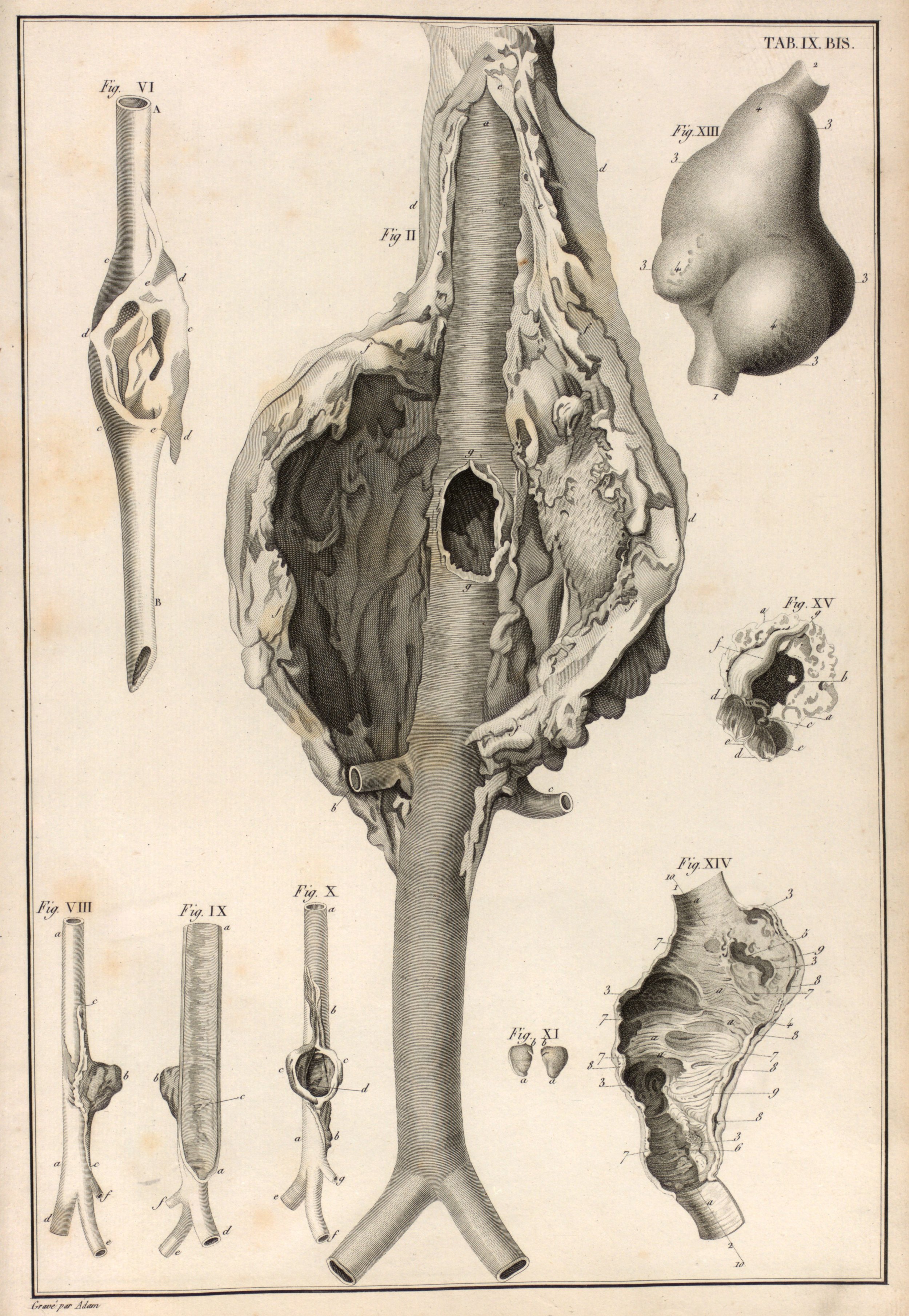

THE QUESTION: IS THERE AN ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSM?

In the Emergency Department, a low threshold for suspecting aortic disease is essential, as the presentation is often nonspecific, and the outcome highly lethal. The prevalence of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) can be higher than 10% in males older than 60 years of age and reach 23% in symptomatic patients; meanwhile, mortality can exceed 90%. A smoking history, male sex, and old age are classic features of AAA; and severe abdominal pain radiating to the back is typically described in the acute presentation. Still, 50% of ruptured AAA patients will lack the classic triad of hypotension, back pain, and pulsatile abdominal mass [4]. To further complicate things, the differential diagnosis is broad, including aortic dissection, renal colic, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, perforated viscus, peptic ulcer disease or acute coronary syndrome. Hence, a high degree of suspicion and timely, accurate detection are needed to overcome the high mortality.

WHY USE ULTRASOUND?

History and physical examination are unreliable in making the diagnosis. Alternative imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT), take time to organize and require the transfer of a potentially unstable patient out of the ED.

The sensitivity and specificity of an emergency physician-US Scan for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) is very high, detecting it in at least 97% of cases (sensitivity 97-100%, specificity 94-100%) [4]. Additionally, if an aortic dissection extends to the abdominal aorta, its characteristic appearance of a mobile “flap” might also be seen.

LIMITATIONS

Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS) comprises a group of serious diseases, including acute aortic dissection, aortic intramural hematoma, and penetrating aortic ulcer. The clinical presentation and features of these processes can be similar or as nonspecific as the ruptured AAA. US can help differentiate between dissection or ruptured aneurysm; however, its sensitivity for aortic dissection is low and not comparable to AAA. Ultrasound is not a reliable tool to rule out aortic dissection, so if suspected, an angio CT study should be arranged. Likewise, US is insensitive in the detection of retroperitoneal blood. If you detect AAA in a shocked patient, assume it has ruptured or is leaking [1]. Furthermore, the differential diagnosis of severe, acute epigastric pain in an unstable patient is broad, and none of these differentials can be accurately diagnosed or ruled out by emergency US.

The presence of bowel gas is frequent and may significantly hinder the acquisition of adequate images. In this case, the application of continued direct pressure with the probe on the abdominal wall may displace the bowel and improve the image. Altering the angle of the transducer may also be helpful. Additionally, obese patients may be very difficult or impossible to scan, yet, tweaking the depth and gain settings could prove useful.

NORMAL

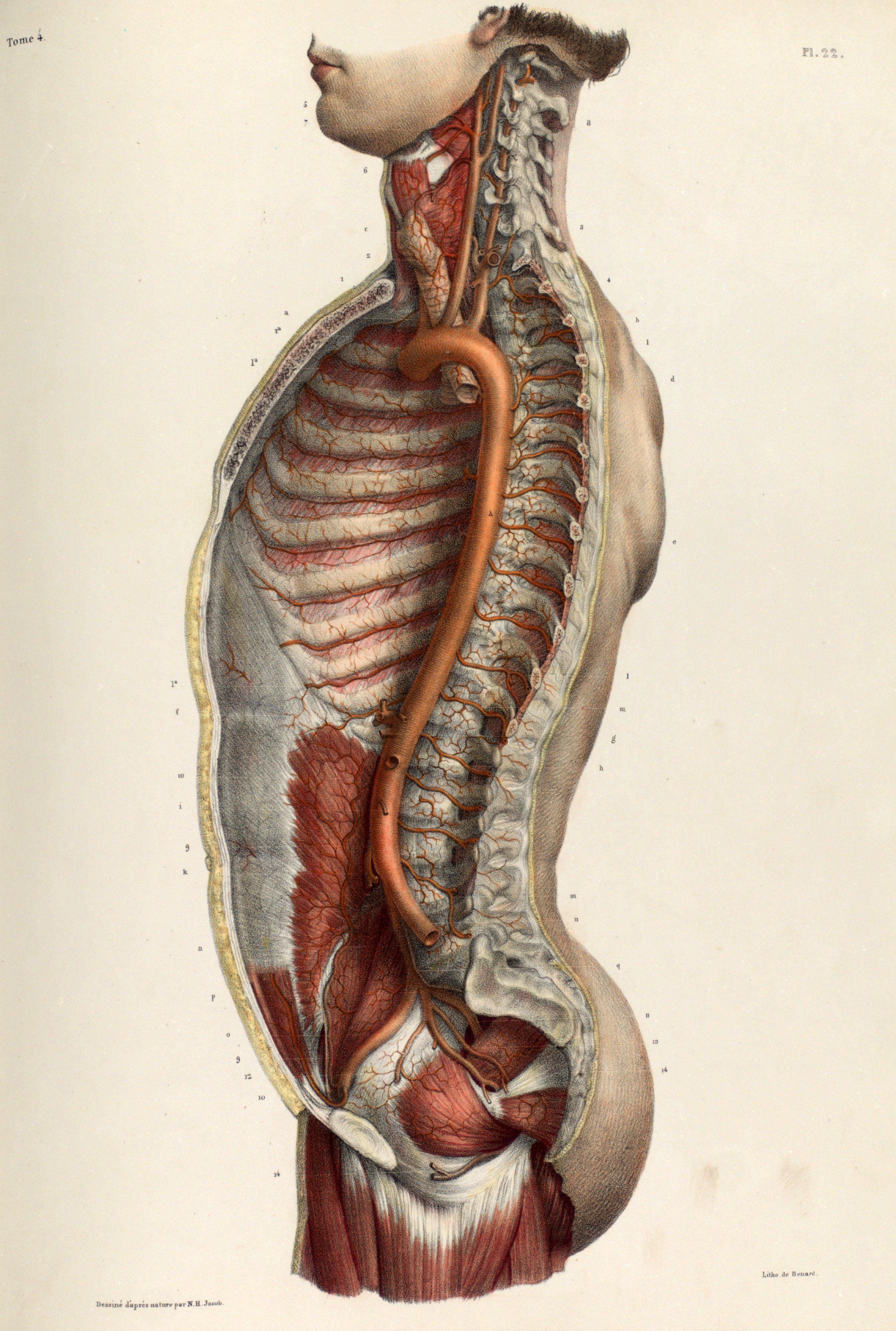

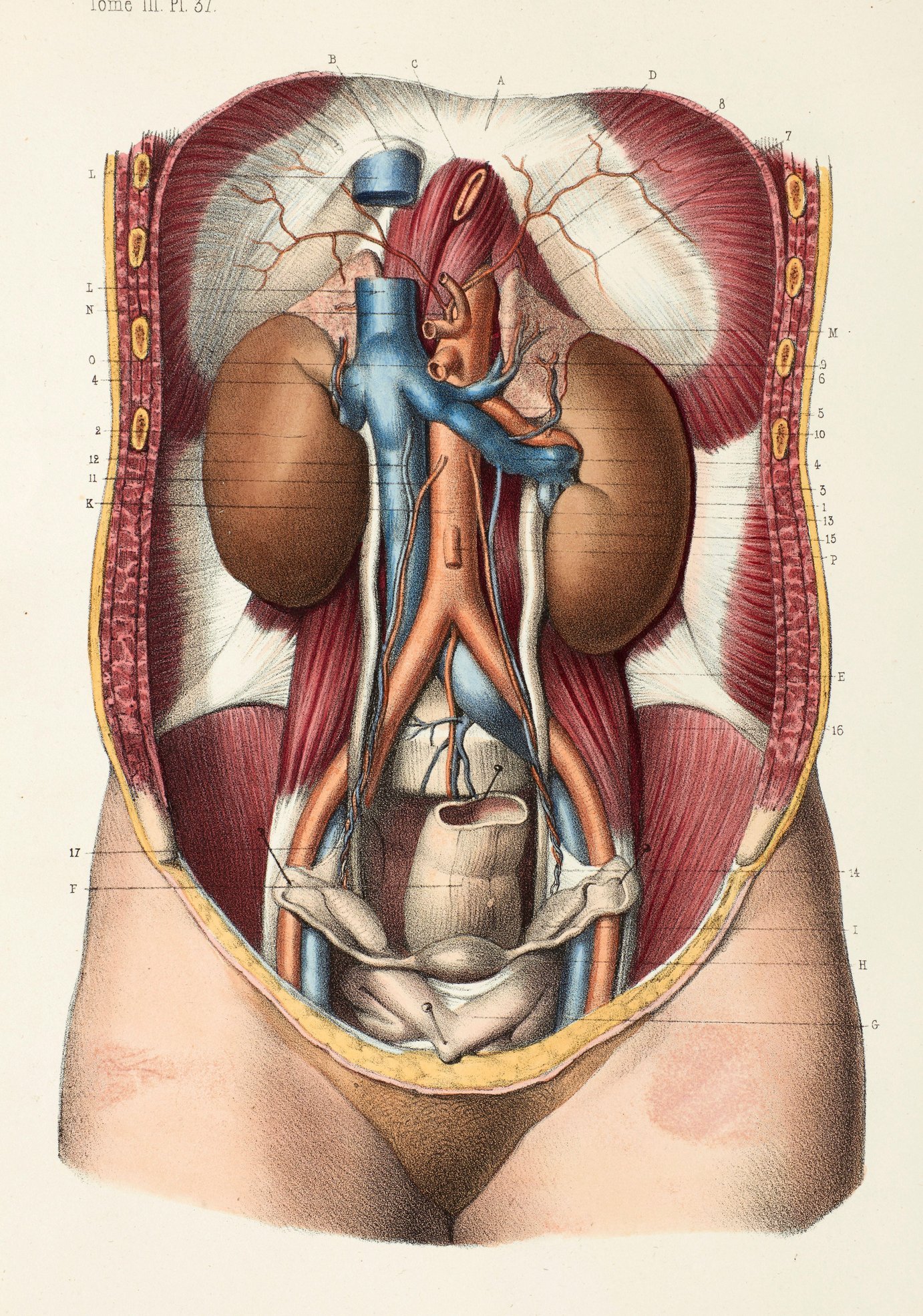

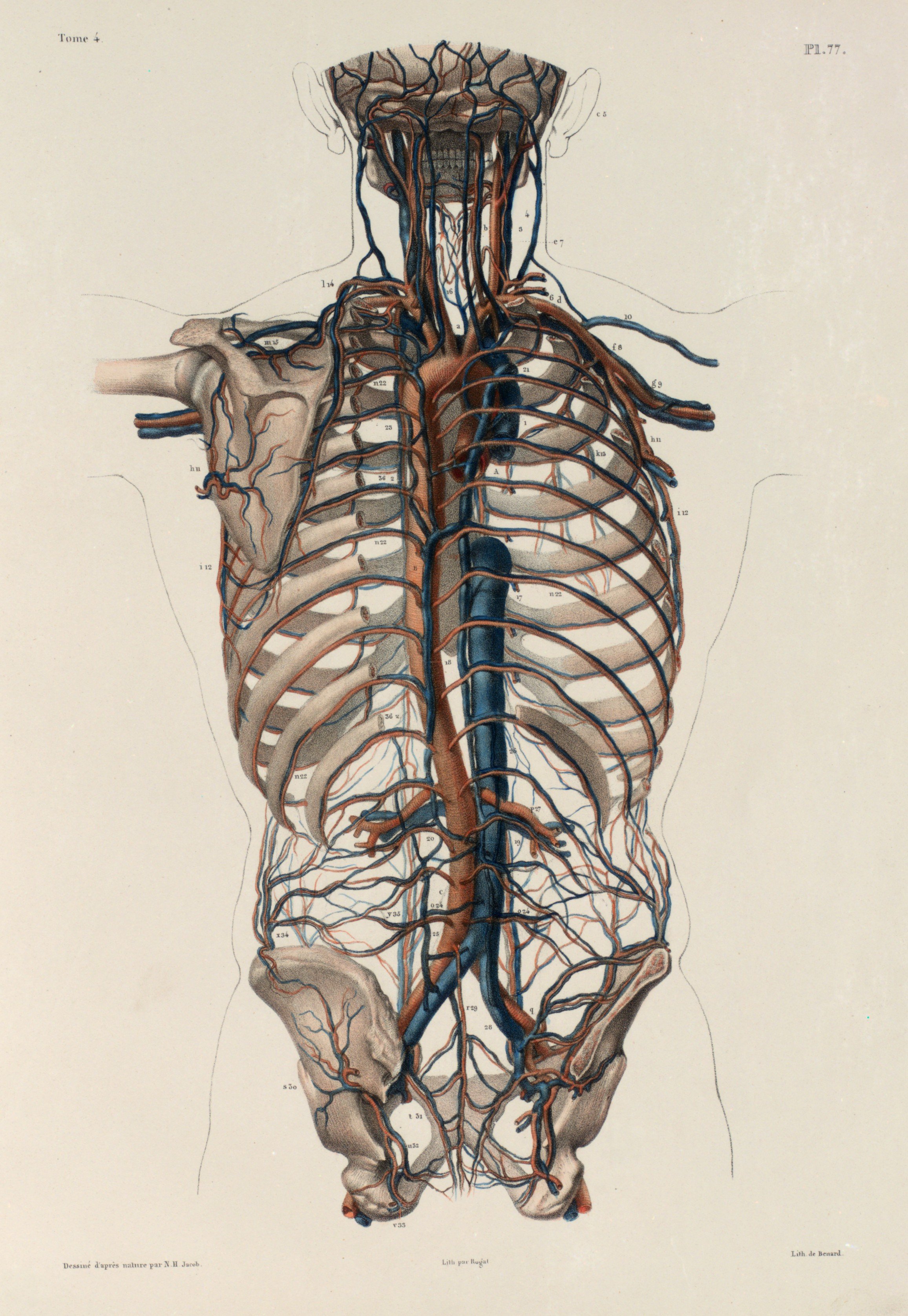

The abdominal aorta lies in the retroperitoneum, directly anterior to the vertebral bodies. It enters the abdomen through the diaphragm at the level of the xiphoid process, narrowing down its diameter as it descends, and then bifurcating into the common iliac arteries at the level of the umbilicus. The aorta gives birth to several branches along its way, yet the most important to identify by ultrasound are the coeliac trunk (common hepatic artery & splenic artery), superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and iliac arteries. The SMA typically originates 1 cm caudal to the coeliac trunk and runs parallel to the aorta. The origin of the SMA is a good surrogate for the level of the renal arteries, which are harder to see on US. For example, if an AAA is seen only below the origin of the SMA, then it is infrarenal. Lastly, the inferior mesenteric artery usually cannot be seen.

Anatomy.

The coeliac trunk (common hepatic artery & splenic artery) and the superior mesenteric artery emerge from the proximal portion of the abdominal aorta. The aorta narrows down as it descends, originating the inferior mesenteric artery, and bifurcates into the iliac arteries.

AORTIC ANEURYSM

In adults, the normal anteroposterior aortic diameter is less than 2 cm, and 3 cm or more is considered dilated. The diameter of the common iliac arteries should not be more than 1.5 cm. Most AAAs occur below the renal arteries. As an aneurysm becomes larger it will dilate faster, leading to a greater risk of rupture. This risk remains low if the diameter is less than 5 cm. By contrast, there is a clear tipping point after surpassing 5.5 cm, as the annual incidence of rupture grows from <1% to 9.4% (5)

Technique & Views.

POSITION & PROBE

As always, the position of the patient will be dictated by the clinical picture. However, a supine position is readily accessible and practical. A low-frequency abdominal probe in standard B-mode setting is ideal. The depth should be configured to 15-20 cm but is adjusted continuously during the scan. Start by placing the probe under the xiphisternum, transverse to the body’s long axis, and with the probe’s marker to the patient’s right

THE VIEWS

To rule out AAA the entire abdominal aorta should be visualized, including a minimum of three transverse images (proximal, middle and distal) and a longitudinal image. All images should be measured from outer to outer wall and saved as backup.

CARDIAC SUBXIPHOID

The initial view is cardiac subxiphoid (as eFAST or SX echo) so the cardiac performance and presence or absence or pericardial fluid can be assessed. The transducer is then transitioned from horizontal to vertical in relation to the body’s axis in order to identify the abdominal aorta in transverse plane.

ABDOMINAL AORTA

Identify the vertebral body, with the aorta directly anterior to it, and adjust the depth and gain settings to optimize visualization. It is essential to identify and differentiate the two major vessels: inferior vena cava (IVC) and aorta. The IVC is parallel and to the right, featuring thinner walls and collapsibility during inspiration. However, owing to transmitted pulsation, it may be misidentified as the aorta, particularly in longitudinal section. The identification of other vessels, namely the coeliac trunk and superior mesenteric artery (SMA), is also helpful for differentiating the aorta from the IVC. The coeliac trunk is conformed by the common hepatic artery and the splenic artery, rendering the classic “seagull sign”.

Once the aorta is identified, measure its diameter from outer to outer wall, as inner wall measurements may underestimate the diameter due to mural thrombus (false negative). While maintaining the transverse orientation, slide the probe distally until the aortic bifurcation and measure the diameter at its middle and distal portions. Then, rotate the probe to the longitudinal position, which is needed to identify saccular aneurysms. Attempt to obtain a view of the aorta that includes the origin of the coeliac trunk or SMA, and measure the AP diameter. Remember, AAA is not ruled out unless the entire length of the abdominal aorta can be visualized and measured.

Areas of bowel gas will be identified and these obstruct the view of the aorta. These areas may be reduced by moving the transducer laterally, rotating the patient or by using the transducer to massage them away from the area of interest. However just keep moving the transducer inferiorly and the aorta will soon be in view again

AAA

AAA GALLERY

Aortic Dissection

AORTIC DISSECTION GALLERY

Bowra, Justin; McLaughlin, Russell; Atkinson, Paul; Henry, Jaimie. Emergency Ultrasound Made Easy, Third Edition. 2022. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Basaure, Carlos; Clausdorff, Hans; Riquelme; Felipe. Ultrasonido Clínico, First edition. 2018. Emergency Medicine Residency Program, Universidad Católica de Chile.

The Pocus Atlas. https://www.thepocusatlas.com

Rubano E, Mehta N, Caputo W, Paladino L, Sinert R. Systematic review: emergency department bedside ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Feb;20(2):128-38. PMID: 23406071

Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, Ballard DJ, Jordan WD Jr, Blebea J, Littooy FN, Freischlag JA, Bandyk D, Rapp JH, Salam AA; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study #417 Investigators. Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA. 2002 Jun 12;287(22):2968-72. PMID: 12052126